Transition

A Site-Specific Multisensory Experience at Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin

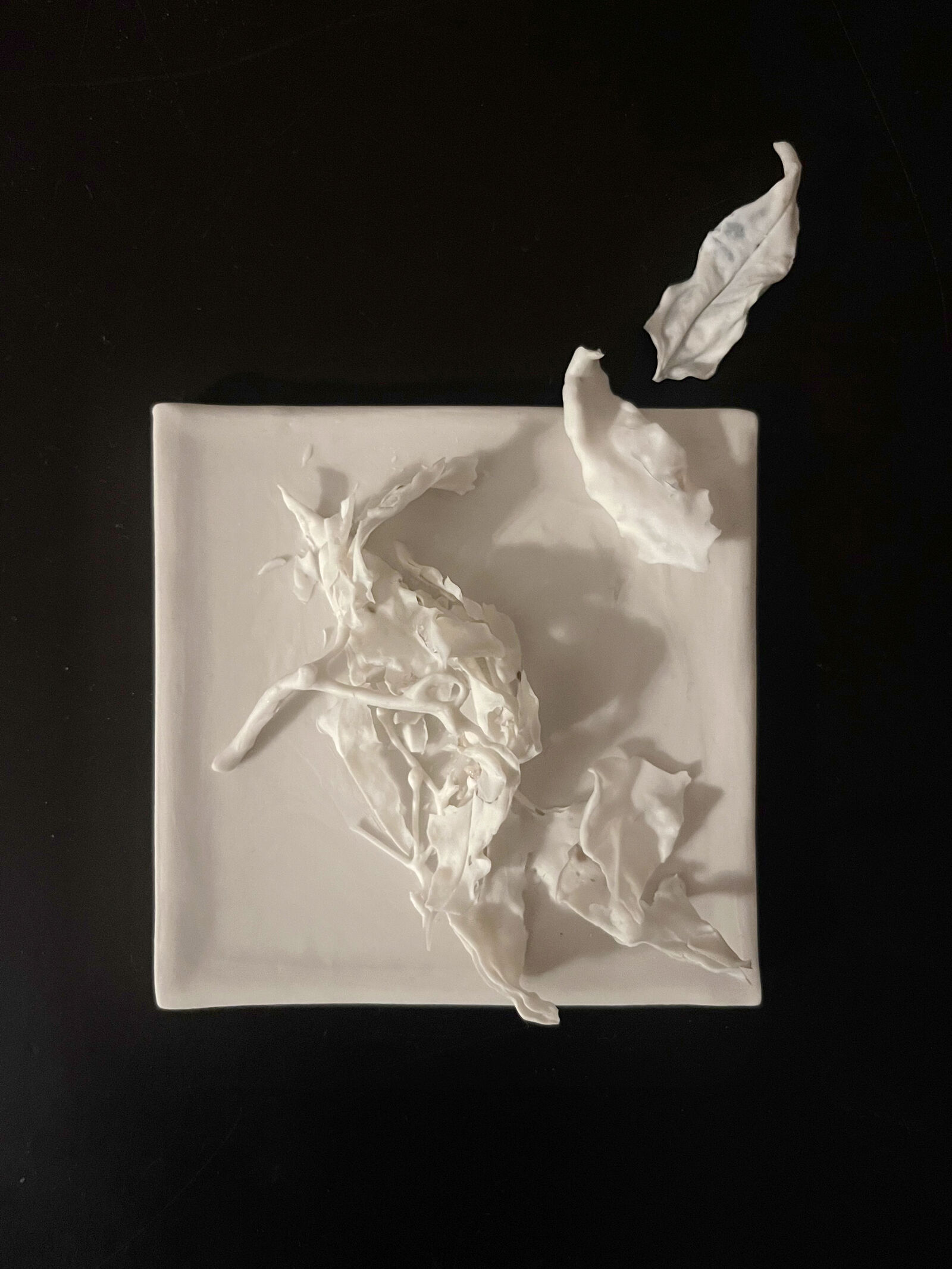

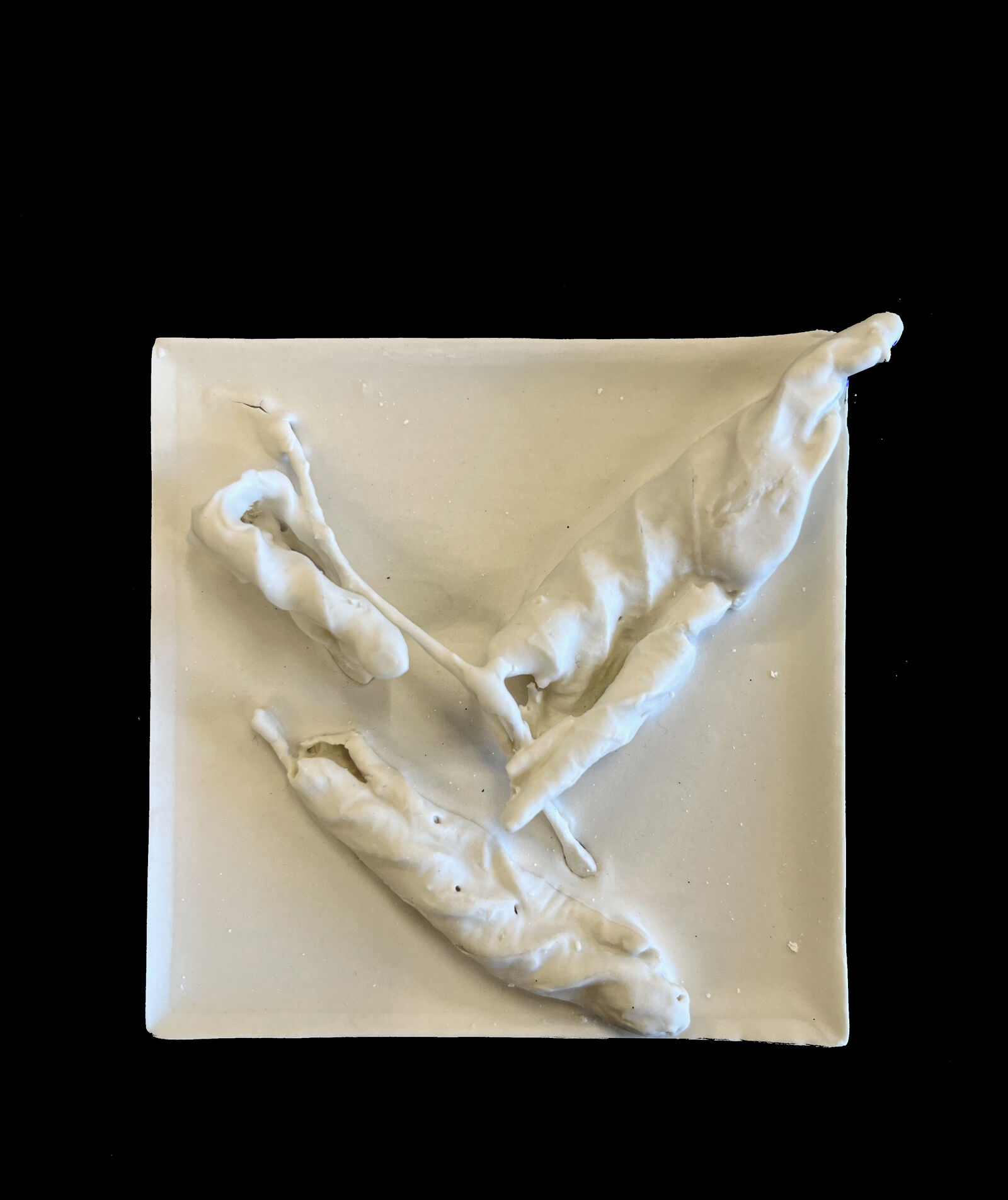

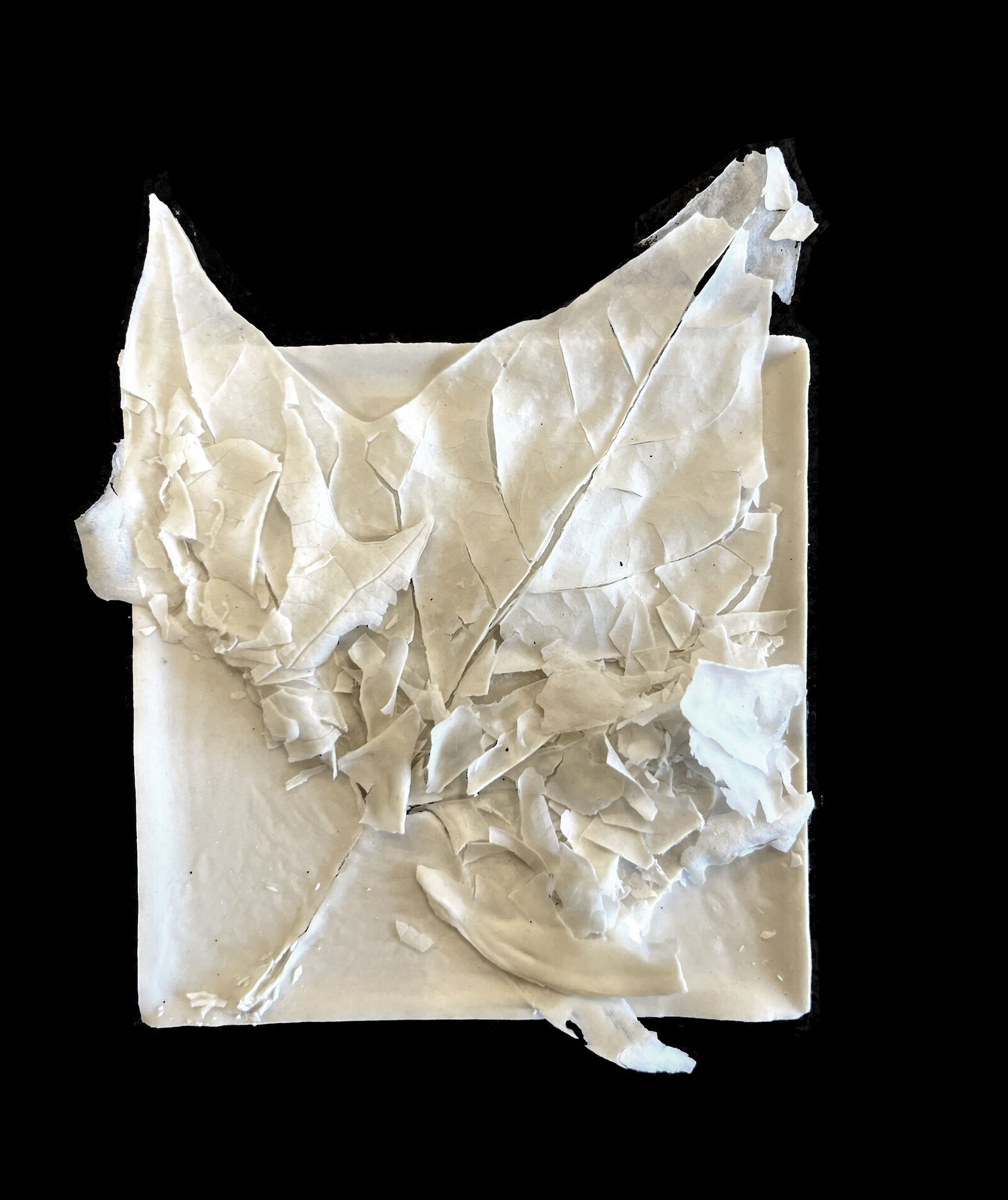

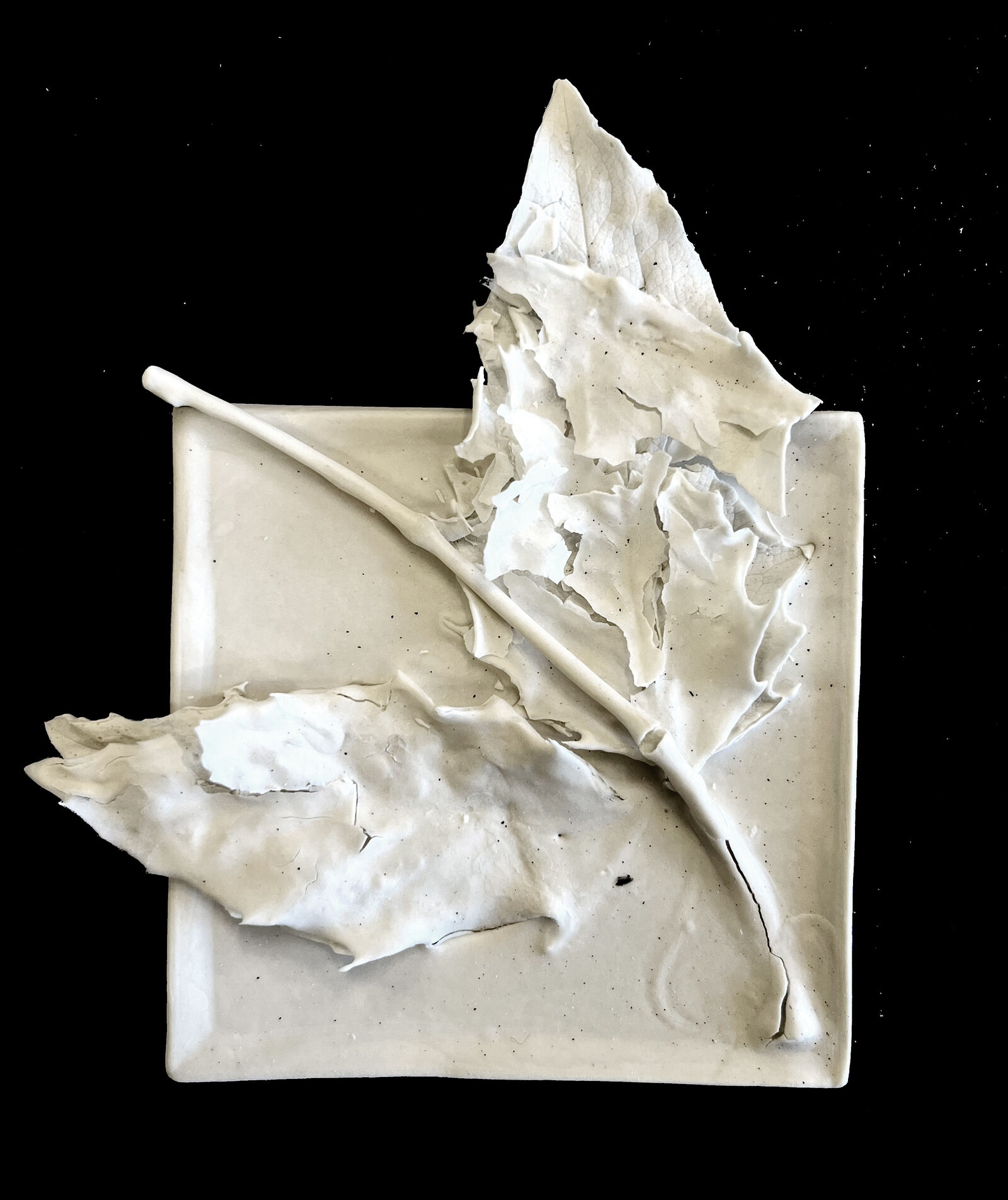

»Transition« is a collaboration between the artist Nuri Kang and the cultural historian Karin Krauthausen for the exhibition Symbiotic Wood (27 June to 21 September 2025) at Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin. The work follows the plants, animals and people that inhabit the periphery of the museum. The porcelain objects of Nuri Kang are crystallized elements of this living world (»Fragmentary Time«), and the audio work of Karin Krauthausen brings together what is found and what is thought in the oral word and thus remains in transition itself.

Photobook

Transition

Going to a museum can be a form of ritual—when we visit an exhibition on our own or with friends in order to have an experience that we can perhaps only have in such a place. But can the act of crossing the museum’s threshold also be described as a ritual? In the sense of a consciously experienced transition to something other? A museum is neither a private space nor a freely accessible urban space. It is neither a home nor a public square. A museum is an enclosed and well-secured institutional space that represents an essential part of what in Western thought is called culture.

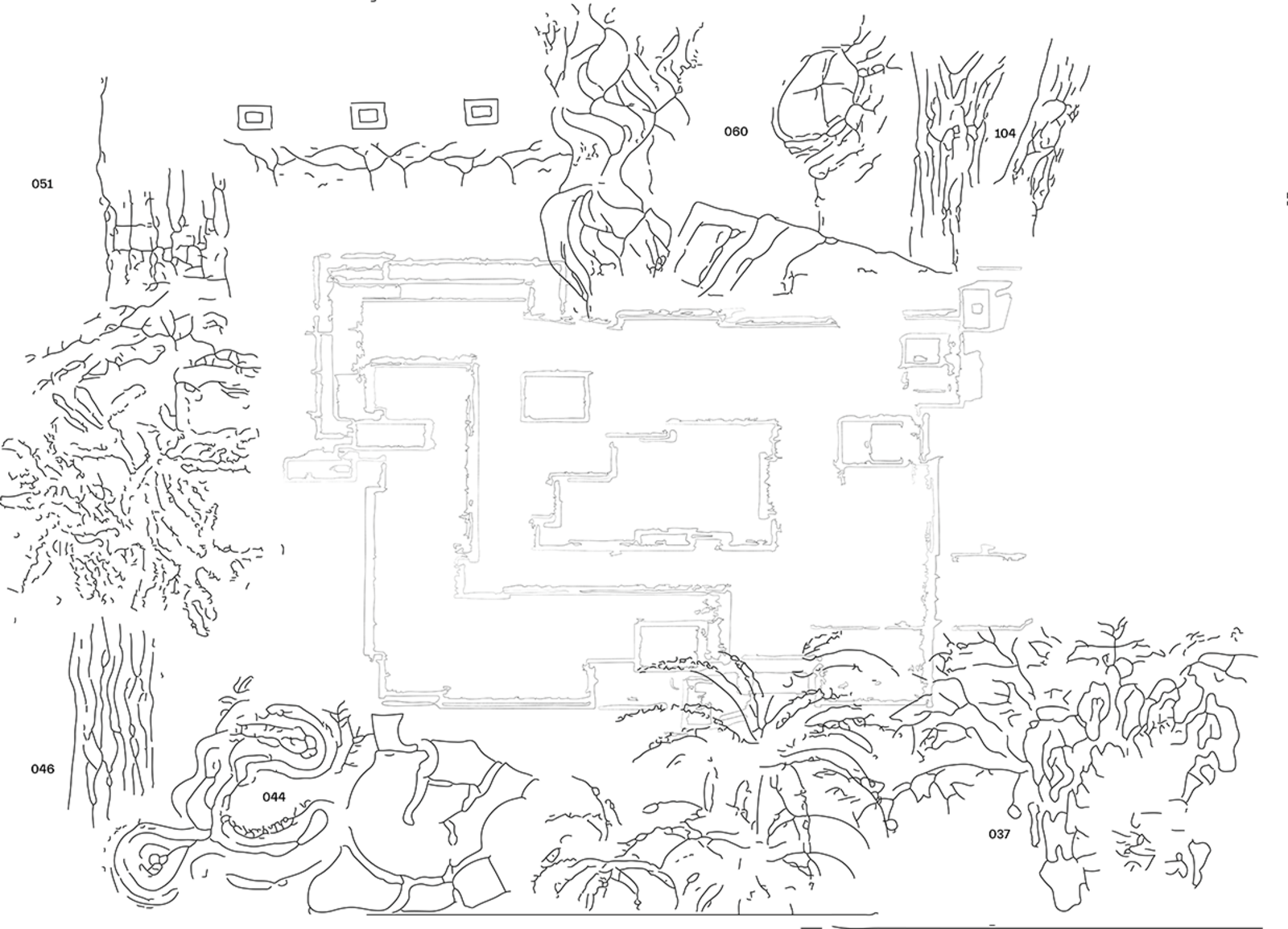

But what happens if I pause on the threshold to such a cultural space? If, instead of entering the Kunstgewerbemuseum, I examine its periphery? The border area of a museum that, forty years ago, was itself built on a political border, one that divided Berlin’s Potsdamer Platz between Germany’s former East and former West? What becomes visible when I explore this threshold, this liminal space, that borders the museum and is intended to regulate the movement of the visitors? This space is neither interior nor exterior, neither exhibition space nor urban space; it is in many ways indeterminate; it’s a place that’s not clearly defined, acting rather as a transition zone. And yet this nonplace is by no means empty. Already the steep flight of steps leading to the entrance and the views from the projecting terraces bring together a number of different levels. The transition zone appears to be composed of many disparate elements, making it difficult to gain an overview of the complex in its entirety.

I wonder whether any plans were made for this peripheral space at the museum’s outer edge? Was a function envisioned for all the folds—the protrusions and recesses—in the outer walls? Who is the small flight of steps hidden away at the bottom of one of the massive sidewalls intended for? And where do the steps sunk into the grass at the rear of the building lead to? A few of the recesses have been secretly repurposed in a way that was surely not part of the original plan and is probably only tolerated: at night these niches provide the homeless with a little privacy and protection from the cold.

There must have been a plan for the adjoining green areas when the museum was first built. The greenery here transforms this liminal space into a decorative setting for the museum’s “actual” exhibits: the treasures displayed inside. But this plan has since been lost and forgotten, and no gardener has been employed to tend regularly to the burgeoning vegetation. Over the years, the planted shrubs and trees have intermingled with newcomers brought by the wind and the birds. Rather than becoming completely overgrown, however, these areas have given rise to an unusual community. Belonging to this heterogeneous community are also several members of the museum staff, some of whom occasionally make themselves comfortable on an old chair placed next to one of the outer walls; some have brought along “vegetal companions,” which they subsequently replanted. One of these companions is the potted palm that has found a new home in a wind-sheltered corner. Indeed, many different things come together in this transition zone: humans and nonhumans, garden culture and wild culture, the individual and the institutional.

If you follow the museums’ outer edges, you will encounter a solitary tree that is much older than the architecture: a so-called London plane—also known as a hybrid plane, since it’s a cross between a Platanus orientalis and a Platanus occidentalis. It has been a common feature in European cities since the seventeenth century, due in part to its strong resilience to pollution and rising temperatures. The crown of this imposing tree is the first thing I see when I walk up the steep flight of steps to the museum’s entrance, since it’s the tree (and not the entrance) that gives me a sense of orientation during my climb. And the plane tree is also my goal when I redescend the steps and continue my tour around the museum’s periphery. It suddenly appears in the middle of the path where the built structure draws back a little to make way. At this point, it is the institution itself that becomes a liminal space, leading me to something else, and this something else is a natural monument: a tree. The hybrid plane doesn’t form an absolute antithesis to the cultural space, however. It represents an overcoming of the culture/nature divide and therefore a kind of transition itself.

Text by Karin Krauthausen. Translation to English by Ben Carter.

Ceramic Works

Audio Work

Credits

Karin Krauthausen, cultural historian (audio work, text, photo book)

Nuri Kang, artist (porcelain objects, drawings)

Iva Rešetar (speaker)

Ben Carter (translation)

Gianpiero Tari, Digital Media – CMS at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (audio recording)

Caspar Pichner, TA T (advisor scenic realization and technique)

Martin Wagner, IT »Matters of Activity (advisor technique)

Carolin Ott & Antje Nestler, PR »Matters of Activity (website and visual advisor)

Richard Ley, PR »Matters of Activity (GIF)

Cluster of Excellence »Matters of Activity«

Keramik Werkstatt der Kunsthochschule Berlin weißensee (KHB)